Katakana Analysis (Revised)

Hi all,

Thanks to everybody who read my katakana analysis draft and commented! Here I have reposted the revised version.

What is the purpose of writing in katakana? In class we read descriptions from various textbooks about the usage of katakana. Most textbooks agree that katakana is used for

(1) loan words borrowed from foreign languages (5 sources)

(2) names (of foreign origin) (4 sources).

A few of the textbooks also mention that it is used for

(3) onomatopoeia (2 sources)

(4) emphasis (1 source)

(5) fashionableness (1 source).

As we see, some textbooks go more into depth about the usage of katakana than others. I think because the last three usages are less common, for an introductory student learning Japanese, it is not necessary to know about them, especially since the last two involve irregular usage of words that would normally be written in hiragana. The beginner student is less likely to encounter material with this sort of katakana usage. Furthermore the katakana descriptions are likely to also express the author's personal interest or intent in providing either a more purely language-focused textbook or a textbook with more cultural background, and also the target audience. A textbook aimed at teaching tourists how to learn Japanese in a few days before they travel there is less likely to mention that katakana is also used as onomatopoeia in manga.

This being said, I would like to look at 2 examples of katakana usage and analyze them in the context of the katakana categories provided above.

The first one is from 水木しげる's manga, 悪魔くん. There is a lot of katakana used throughout the manga to express onomatopoeia. Interestingly, many of the textbook examples we read describing katakana usage mention its usage in loanwords and names but not onomatopoeia (two of them do). Below we see a picture where katakana ("dododo-n", "meri-meri-meri", etc.) are used to describe the sounds of thunder and a tree splitting in a storm, respectively. This is classical use of onomatopoeia. The angular shape of the katakana also lends itself well to expressing the harshness of thunder, and it is drawn in such a way (boxy, asymmetric) that mimics the look of lightning, adding emotional effectiveness to the manga scene.

Furthermore, the sound effects throughout the same manga can shift from katakana to hiragana or even Roman letters (see the two examples below). The "ton ton" of a door knock is written in hiragana; the sound it is expressing is also a much softer, more welcome sound. The softer visual look of the hiragana in this case is more appropriate. Another thing is to consider is that door-knocks are sounds made by people. Would it be too far-fetched to suggest that onomatopoeia, which usually consists of sounds produced by nature, machines, inanimate objects, etc. constitutes some kind of "foreign language"? In class, we looked at other uses of onomatopoeia in manga on classmates' blogs. On Yunfei-san's blog (http://feiiifei.blogspot.com/) we saw hiragana onomatopoeia being used for the "aaaa's" of a crowd. It seems that when hiragana is used for onomatopoeia, it is used for more "familiar" sounds produced by people, hence being part of the "native language" of humans. Of course, katakana is also used for sounds produced by humans, so this is not an exclusive rule, just a tendency.

Finally, Roman letters are occasionally used in the manga for onomatopoeia as well. In the following example, it is used alongside katakana ("buruburu" - planes' wings, "parapara" - bombs dropping). It is interesting to note that Roman letters are reserved for the most devastating sound effects and are also written in the largest script. Because of their foreign look, and also capacity for more consonantal sounds (a later example in the book has "DGAAN") they seem to be used in cases where the author wants to express katakana sounds in EXTREME FORM - bombs hitting the earth, etc. Furthermore katakana onomatopoeias are common enough that there is a list of common usage for them - Roman letters are reserved for more unusual sounds of large impact - also the sounds farthest from what would be produced by a human!

In conclusion, from our first example we see that katakana is used often in onomatopoeia, due to its strong visual effect and alien-ness (to distinguish from human speech). But it is not used exclusively - it can be replaced by hiragana or Roman letters when a softer or a stronger impact is needed, respectively. Sometimes writing in katakana is compared to writing in bold or italics in English, but I think it is more than that! Look at the interesting variation creating by using italic katakana in a regular square script that creates the look of motion:

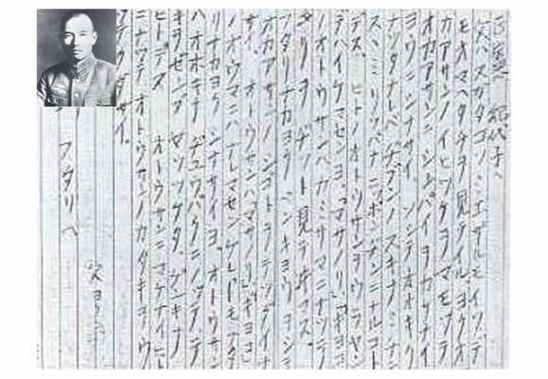

My next katakana example is from a famous poem by the early 20th-century writer 宮沢賢治. It is called 「雨ニモマケズ」(Be strong in the rain). Below is a picture of the original manuscript which was found posthumously in one of the poet's trunks:

As we see, the poem is nearly entirely written in katakana with a few kanji. This is problematic since the majority of the poem is native Japanese that would nowadays be written in hiragana. This usage of katakana does not fall cleanly into any of the 5 categories mentioned above.

The mystery is solved if we consider the historical context of this poem. It was written before 1946 when the Japanese cabinet standardized orthography. Before that it seemed people had a lot more freedom in writing what kind of kana they pleased. Hiragana which is softer and rounder was often seen as "woman's writing" (mentioned in the one of the textbook sources) while kanji and katakana used in conjunction was often used by men. A-ha, we say, the writer of this poem was a man, and hence he uses kanji and katakana here. Simple enough.

I think there may an alternate way of looking at this, however. After all, not all men wrote in kanji and katakana, and the Wikipedia article on hiragana mentions that hiragana was also used by male authors in literary works and in personal letters (because it is faster to write). Given that this is a poem found in somebody's personal trunk, there is no reason also why it could not have been written in hiragana.

I did some more research on this and found that poetry, which is "beautiful language" was apparently more often written in hiragana which lends itself better to calligraphy. The beautiful harmony of kanji and hiragana which look good together is called "chouwatai" (調和体) (see http://www.beyondcalligraphy.com/kana_part_2.html). For example, here is waka poetry written by Emperor Meiji which comes from the same era:

Looking at the historical usage of kana may give us some clues. Katakana was developed in the Heian era by Buddhist monks to add glosses to the sutras. While hiragana, a kind of cursive writing, was useful because it was fast to write, katakana was useful because it was small enough to fit in the margins of sutras and highly readable. The aura as a whole is more austere and formal than hiragana.

Other interesting katakana examples from the late 19th century-early 20th century include the Meiji constitution (it is a formal legal document - there is a picture on the class blog) and this last letter written by a kamikaze pilot to his children. Children were taught katakana in the lower levels of school and it was easier for them to read.

Returning to Miyazawa Kenji's poem, the translation can be found in two versions here:

http://tomoanthology.blogspot.com/2012/08/kenji-miyazawas-poem-ame-ni-mo-makezu.html

Reading it, I think it is an epitaph on the poet's life. He was of poor health throughout his lifetime and probably knew he was going to die (so he writes that he wishes to have a strong body). It is probably appropriate then that because what he is saying is so very important to him and very meaningful, to use the more formal katakana. If he intended eventually to publish the poem and let others read it, it would also be more readable to people who have had less education, so as to get his message across. In a way, it is a poetic analog to the last letter of the kamikaze pilot. From a modern point of view, the look of poem is very striking, not unlike the punctuation-less English poems of e.e. cummings.

In short, katakana is a useful system for delineating foreign names and loan words, but its usage in the Japanese language is not limited to those cases. What I think is important to remember is that originally there was no set rule! Katakana has a different look, which the Japanese have decided is appropriate for different instances. What I got from looking at my classmates' analyses is that katakana is now increasingly being used for novel purposes due to it sense of modernity and fashionableness. Who knows if in the future the rules for using kana will change?

シワ